Earth Sustaining Symbiotic Biotechnology

Earth Sustaining Symbiotic Biotechnology

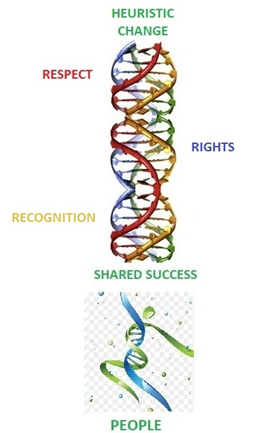

Heuristic Change focuses upon the enabling someone to discover or learn something for themselves: A Hands-on or interactive heuristic approach to learning and sharing. Heuristics are efficient mental processes (or mental shortcuts) that help humans solve problems or learn a new concept. In the 1970s, researchers Amos Tversky, and Daniel Kahneman identified three key heuristics:

Heuristics are the strategies derived from previous experiences with similar problems. These strategies depend on using readily accessible, though loosely applicable, information to control problem solving in human beings, machines, and abstract issues. The concept of Heuristics was originally introduced by the Nobel laureate Herbert A. Simon, whose original, primary object of research was problem solving that showed that we operate within what he coined the term satisficing, which denotes a situation in which people seek solutions, or accept choices or judgements, which are good enough for their purposes although, they could be optimised. The study of heuristics in human decision making was developed in the 1970s and the 1980s by the psychologists Amos Tversky, and Daniel Khaneman. When an individual applies a heuristic in practice, it generally performs as expected. However, it can alternatively create systematic errors. The most fundamental heuristic is trial and error, which can be used in everything from matching nuts and bolts to finding the values of variables in algebra problems. In mathematics, some common heuristics involve the use of visual representations, additional assumptions, forward/backward reasoning, and simplification.

RESPECT IN HEURISTIC CHANGE

Respect must be bilateral, it must be earned, and it must be honoured

The concepts are also invoked in bioethics, environmental ethics, business ethics, workplace ethics, and a host of other applied ethics contexts. Although a wide variety of things are said to deserve respect, contemporary philosophical interest in respect has been overwhelmingly focused on respect for persons, the idea that all persons should be treated with respect simply because they are persons. Respect for persons is a central concept in many ethical theories; some theories treat it as the very essence of morality and the foundation of all other moral duties and obligations. This focus owes much to the 18th century German philosopher, Immanuel Kant, who argued that all and only persons (i.e., rational autonomous agents) and the moral law they autonomously legislate are appropriate objects of the morally most significant attitude of respect. Although honour, esteem, and prudential regard played important roles in moral and political theories before him, Kant, was the first major Western philosopher to put respect for persons, including oneself as a person, at the very centre of moral theory, and his insistence that persons are ends in themselves with an absolute dignity who must always be respected has become a core ideal of modern humanism and political liberalism. In recent years, many people have argued that moral respect ought also to be extended to things other than persons, such as nonhuman living things and the natural environment. Despite the widespread acknowledgment of the importance of respect and self-respect in moral and societal life and theory, there is no settled agreement in either everyday thinking or philosophical discussion about such issues as how to understand the concepts, what the appropriate objects of respect are, what is involved in respecting various objects, what the conditions are for self-respect, and what the scope is of any moral requirements regarding respect and self-respect.

RIGHTS IN HEURISTIC CHANGE

It is the duty of every individual to develop a societally positive commitment to common rights and the change of lesser optimal rights to appropriate rights.

RECOGNITION IN HEURISTIC CHANGE

Recognition is positive acknowledgement earned through the demonstration of worthy character.